Section 5 :: Predation

Calculating Profitability as a function of the number of encounters

Let’s consider the equation for profitability that we discussed earlier in the semester

\[\begin{equation} P = \frac{E_{\rm net}}{T} \end{equation}\]where \(E\) is the net energy gain, and \(T\) is time. We added some complexity when we considered profitability of a particular foraging bout given the probability of successfully obtaining a particular resource, such that

\[\begin{equation} P = \frac{\phi E_{\rm success} + (1-\phi)E_{\rm fail}}{\phi T + (1-\phi)W} \end{equation}\]where \(\phi\) was the probability of success, \(E_{\rm success}\) was the net energetic gain associated with the probability of success, \(E_{\rm fail}\) was the net energetic gain associated with a failure, \(T\) was time spent foraging during a successful bout, and \(W\) was time spent foraging during an unsuccessful bout. Moreover, we originally assumed that \(E_{\rm fail} = 0\), simplifying the numerator of the equation.

In this context, we were considering the profitability of a particular foraging bout. Now let’s consider profitability over the course of an entire day. We will assume that a predator consumer has various numbers of encounters with a particular prey species. If it successfully encounters and captures a single prey species, it fills its stomach and obtains \(E_{\rm gain}\). However when considering net energetic gain, we also have to consider the metabolic cost. So if \(\phi\) is the probability of successfully encountering and capturing at least one prey within a day, the equation will become

\[\begin{align} P &= \frac{\phi(E_{\rm gain} - E_{\rm cost}) + (1-\phi)(-E_{\rm cost})}{\phi T + (1-\phi) W} \\ \\ P &= \phi(E_{\rm gain} - E_{\rm cost}) + (1-\phi)(-E_{\rm cost}) \end{align}\]Discussion

- Why does the denominator in the above equation disappear? What are the units and values of \(T\) and \(W\)?

- What is our interpretation of \(\phi\)?

- What is our interpretation of \(E_{\rm gain}\) and \(E_{\rm cost}\)?

In the above profitability equation, \(\phi\) is generally defined… it is just the probability that at least one prey is killed and consumed over the course of the day. But we can do a bit better than this. We might assume that \(\phi\) should change with the number of encounters between the predator and it’s targeted prey. As the number of encounters increases, the likelihood that it captures at least one individual should increase. Likewise, if it encounters very few individuals, the probability of success over the course of the day should decline.

Let’s write \(\phi\) in terms of the number of encounters the predator has with its prey over the course of a day. We need to consider two things:

- the number of encounters \(n\)

- the probability of successfully capturing a prey within a single encounter \(s\).

First, start with one encounter… if there is just one encounter then \(\phi = s\). Now consider two encounters… this is a bit more complicated. Because \(\phi\) is just the probability of any successful encounter, there are a number of things that can happen:

- A first success and then a second success with probability \(s \cdot s = s^2\)

- A success and then failure with probability \(s(1-s)\)

- A failure and then a success with probability \((1-s)s\)

- A first failure and then a second failure \((1-s)(1-s)\)

Discussion

- Why do the above events have the probabilities given? Convince yourself that you understand why.

- If we consider the probabilities of all things that can potentially occur, they have to add up to one. Do the above events add up to one?

As we see from above, a single encounter is simple and there are two things that can occur… succeed with probability \(s\) or fail with probability \((1-s)\). Two events are more complicated, as more sequences of events can occur. And as you might expect this gets worse with more and more encounters. However, there is a nice little trick we can employ. All we really care about is whether or not at least one encounter is successful. With regard to the two encounters described above, we care about whether possibilities 1-3 occur. In other words, we just want to know when the predator does not fail. This makes the problem easier, because the probability that the predator does not fail is just \(1 - (1-s)(1-s) = 1 - (1-s)^2\). In fact, this gives us a general formula for the probability of a least one success, which is

\[\begin{equation} \phi = 1 - (1-s)^n \end{equation}\]Discussion

- Describe in words this new equation for \(\phi\)

- What is the role of \(n\) here? Recall that \(n\) is the number of encounters

Now let’s put together our new Profitability equation over the course of a single day with varying numbers of encounters. We now have

\[\begin{align} P &= \phi(E_{\rm gain} - E_{\rm cost}) + (1-\phi)(-E_{\rm cost}) \\ \\ P &= (1 - (1-s)^n)(E_{\rm gain} - E_{\rm cost}) + (1-s)^n(-E_{\rm cost}) \end{align}\]Let’s examine how profitability increases as a function of the number of encounters:

# Define a sequence for number of encounters

n = seq(1,20)

#Define other parameters

#Probability of success

s = 0.1

#Daily energetic gain of at least one success (max intake)

Egain = 4000 #kilocalories

#Daily energetic cost

Ecost = 2000 #kilocalories

profitability = (1 - (1-s)^n)*(Egain - Ecost) + (1-s)^n*(-Ecost)

#Plot relationships between Profitability and number of encounters

plot(n,profitability,xlab="Number of encounters",ylab="Profitability (kcal/day)",type='b')

Discussion

- Describe the relationship that you observe in words. How does profitability depend on the number of encounters?

- This is of course ‘average profitability’ given that we are dealing with probabilities. On average, how many encounters does the predator need to have in order to break even? By break even we mean that there is no gain and no loss in terms of profitability.

- What attributes of prey and predator would be expected to impact the number of encounters per day? Recall from lecture notes.

- Experiment with different values of the parameters, and in particular the ‘break-even number of encounters’ vs. \(s\).

One last interesting point… the break-even point as defined above is when profitability is zero \(P=0\)… this means that the amount gained is equal to the amount lost (given that we are accounting for both energetic gains and losses through a day). We can solve for this point explicitly in terms of the break-even value of \(s^*\), which we denote as being ‘special’ with the asterisk (\(*\)).

\[\begin{align} P &= (1 - (1-s^*)^n)(E_{\rm gain} - E_{\rm cost}) + (1-s^*)^n(-E_{\rm cost}) \\ \\ 0 &= (1 - (1-s^*)^n)(E_{\rm gain} - E_{\rm cost}) + (1-s^*)^n(-E_{\rm cost}) \\ \\ s^* &= 1 - \left(\frac{E_{\rm gain} - E_{\rm cost}}{E_{\rm gain}}\right)^{\frac{1}{n}} \end{align}\]Discussion

- By setting the profitability equation to zero, try to solve for \(s^*\) and derive the solution shown above on your own.

- What do you think this will show? Will \(s^*\) increase or decrease with the number of encounters \(n\)?

- Examine the relationship below, and then try to justify the relationship with an ecological argument…

- Which is the more successful predator? To be an incredibly skilled hunter, or to increase your encounter rate with prey?

# Define a sequence for number of encounters

n = seq(1,20)

#Define other parameters

#Daily energetic gain of at least one success (max intake)

Egain = 4000 #kilocalories

#Daily energetic cost

Ecost = 2000 #kilocalories

#The break even probability of success for a single encounter

breakevensuccessprob = 1 - (-((Ecost - Egain)/Egain))^(1/n)

#Plot relationships between Profitability and number of encounters

plot(n,breakevensuccessprob,xlab="Number of encounters",ylab="Break-even success probability",type='b')

The Lotka-Volterra Predation System

As we have investigated the dynamics of two species engaged in competitive interactions with each other, we will now use the same methodology to investigate two species engaged in a predator-prey interaction. There is one important difference here: while the Lotka-Volterra competition system is entirely symmetric (the equation for competitor \(N_1\) mirrors the equation for competitor \(N_2\)), we have to consider very different forms for the predator and prey because they interact in different (asymmetric) ways.

There are four important processes that the predator and prey equations need to capture:

- The prey species \(N\) grows exponentially in the absence of the predator

- The prey species \(N\) has a mortality caused by the predator

- The predator species \(P\) grows by consuming the prey

- The predator species \(P\) has a constant mortality rate

Let’s put these elements together into a 2-dimensional dynamic system, where we are tracking both the prey \(N\) and predator \(P\) population densities over time.

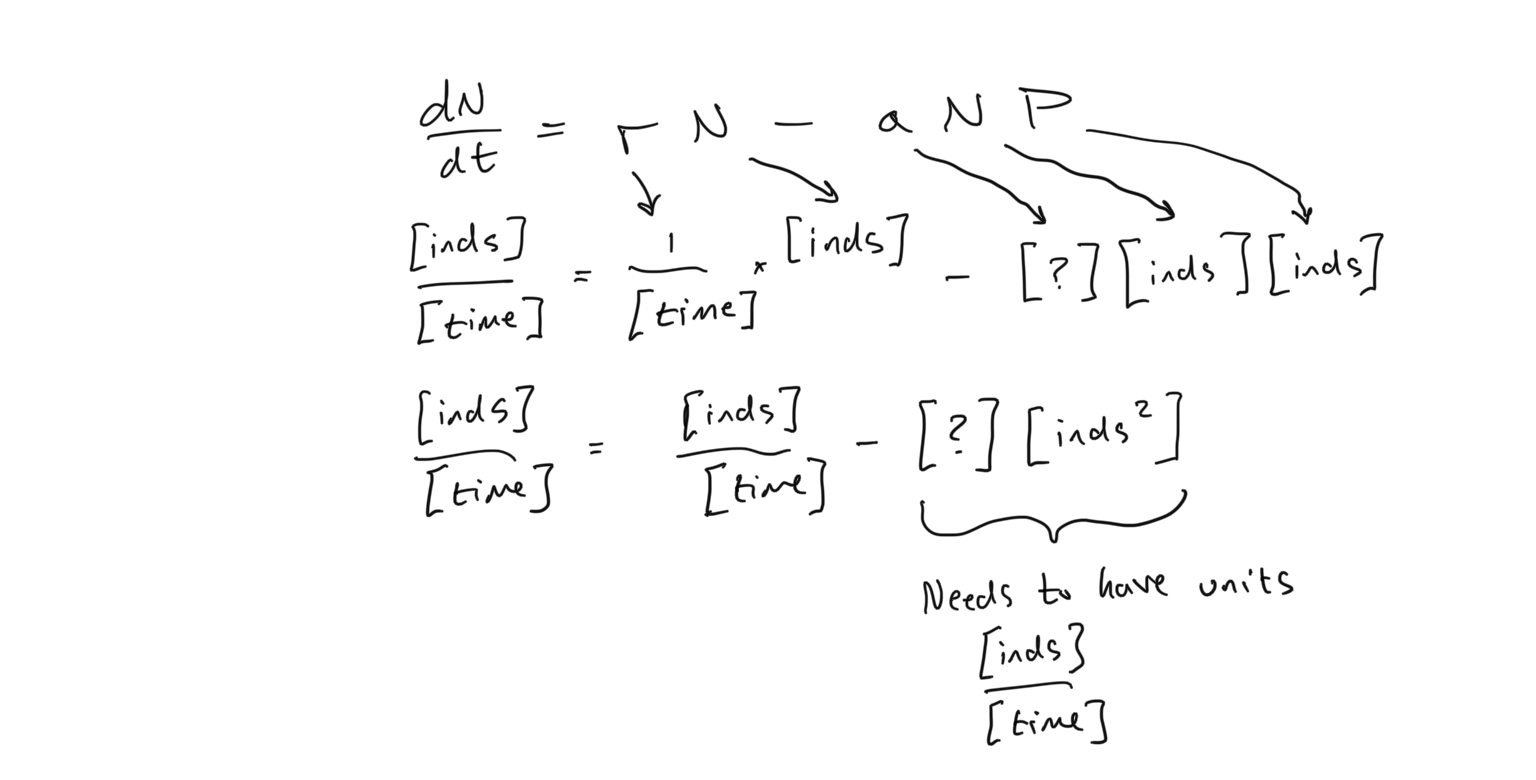

\[\begin{align} \frac{\rm d}{\rm dt}P &= baNP - mP \\ \\ \frac{\rm d}{\rm dt}N &= rN - aNP \end{align}\]Discussion

- What are the different parameters in this model, and before you read on, what do you think they mean?

- What are the units of the different parameters in this model?

- If the predator population goes extinct, what is the equation for the prey population?

- If the prey population goes extinct, what is the equation for the predator population? How does this differ from the equation for the prey population under the predator extinction condition?

What are the parameters in the LV Predator-Prey system and what do they mean?

Let’s examine the different parameters that we have to consider. Let’s begin with the prey population \(N\) because one of the parameters here are already familiar to us. First, we see that the prey population \(N\) grows exponentially in the absence of a predator. The parameter \(r\), as before is the instantaneous rate of growth and has units of \(1/[time]\). The parameter \(a\) is new to us, however, and it’s units are not clear. Let’s examine the units for all of the parameters to see if we can build insight into what \(a\) represents. The central rule here is that the units of the left hand side must equal the units of the right hand side. Also it is important to remember that if we add quantities with the same unit, the result will have the same unit… in other words, if \(N\) has units of \([individuals]\) and \(P\) has units of \([individuals]\), then \(N+P\) has units of \([individuals]\). However if the terms are multiplied or divided by each other, the units take on the results of those operations. So \(N\cdot P\) has units of \([individuals^2]\)

Discussion

- What are the units of \(a\) given the unit analysis presented above? Observe that the terms \(aNP\) must have units of \([individuals]/[time]\) so that the units on the LHS (Left Hand Side) equals the units on the RHS (Right Hand Side).

- What does it mean for the change in \(N\) over time if \(a\) is large? If it is small? If it is zero? How does this aid your interpretation of its role in the LV Predator-Prey system?

As we observe in the above comparison of parameter and variable units on both sides of the equation, this new parameter \(a\) must have units of \([1/(time \times individuals)]\) for the units on both sides of the equation to match. And as you should be able to guess given the impact on \(dN/dt\) as \(a\) is increased or decreased, a larger \(a\) means that the growth of the prey is slowed down, and a smaller \(a\) means that the growth is increased. The meaning of \(a\), which will be more apparent when we examine the equation for predator growth, is the capture efficiency of prey by the predator. If a predator is more efficient (higher \(a\)), it captures more prey individuals per unit time. So the predator is more efficient at extracting prey biomass to create more predator individuals. In other words, there are more captures per prey per unit time (which corresponds to the units for \(a\) that we derived above). Now let’s examine the entire quantity \(-aNP\). From this we see that if there are more predators \(P\), there is more prey biomass taken away (and the growth of the prey declines), and that this amount scales with the population size of the prey \(N\).

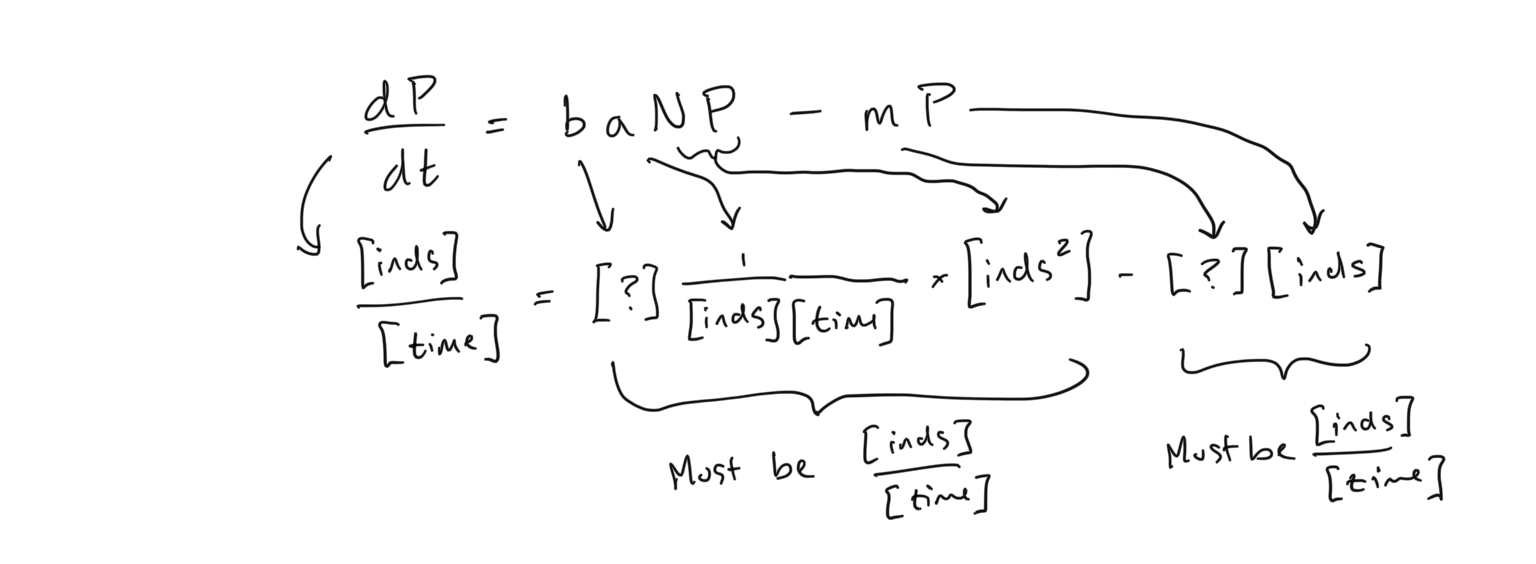

Taking what we know about \(a\), let’s examine the units of the predator equation

Discussion

- From this analysis of units, what units do the parameters \(b\) and \(m\) have?

- What is your interpretation of \(b\)?

- What is your interpretation of \(m\)?

- Do you suspect that any of the parameters in the Lotka-Volterra predator-prey system might be unitless?

- If the parameters \(r\), \(a\), \(b\) and \(m\) are higher vs. lower, how would this impact the growth of the predator population \(P\), and the prey population \(N\)? Hint: list each parameter and denote whether it has an increasing or decreasing effect on predator and prey population growth.

The parameter \(b\) is often called the conversion efficiency and varies between 0 and 1. As we can see above, whatever is taken from the prey population by the function \(-aNP\) is added to the predator population by \(+baNP\). If \(b\) varies between 0 and 1, we can see that not all biomass taken from the prey population becomes new predator biomass, and this is because much of the potential energy is lost during transfer as heat. In fact, we often assume that \(b \approx 0.1\) in most predator-prey interactions, though this number can vary substantially. It is also one of the primary reasons we are more likely to run into herbivores when out for a hike than we are to run into predators!

Discussion

- Let’s assume the ‘prey’ that we are considering is a plant species, and the ‘predator’ is an herbivore. Would \(b\) be expected to by higher or lower relative to \(b\) for a carnivore eating an herbivore? Why?

- What is the per-capita birth rate for the Predator population in terms of the parameters in the LV predator-prey system?

- What is the per-capita mortality (death) rate for the Predator population?

- What is the per-capita birth and mortality rates for the Prey population in the LV predator-prey system? (Note that for questions 2-4 the answer may be a single parameter or a combination of parameters/variables).

In summary, the Lotka-Volterra Predator-Prey system describes a prey population that grows exponentially in the absence of the predator, but that suffers mortality due to predation. On the other side, we have a predator population whose growth is tied to its consumption of the prey population… the more it consumes the higher its \(dP/dt\). The predator population cannot grow forever, as it suffers some amount of mortality proportional to its population size.

Assessing the dynamics of the LV Predator-Prey system

Now that we have a better understanding of the Lotka-Volterra system and the parameters involved, let’s deploy the same tools that we used to investigate the LV competition system to understand the dynamics here. First, recall the steps required to reconstruct the dynamics of a 2-dimensional system:

- Set the \(d/dt\) equations to 0 to solve for the steady state. These will be the equations for the isoclines of the system. Here we will be finding the prey isocline (where \(dN/dt = 0\)) and the predator isocline (where \(dP/dt = 0\)).

- Find the x- and y-intercepts of the prey and predator isoclines so that we can plot them in the coordinate space where the density of prey, \(N\), is on the x-axis and the density of predators, \(P\), is on the y-axis.

- Determine the flow in the 2-dimensional space by solving for prey growth \((dN/dt > 0)\), prey decline \((dN/dt < 0)\), predator growth \((dP/dt > 0)\), and predator decline \((dP/dt < 0)\).

- From the flow along the \(N\) and \(P\) axes (i.e. flow along the horizontal and vertical axes, respectively), find the composite flow (i.e. flow along the diagonal directions).

- The composite flow will tell us how the population densities of prey \(N\) and predator \(P\) change over time, as well as the final state of the system.

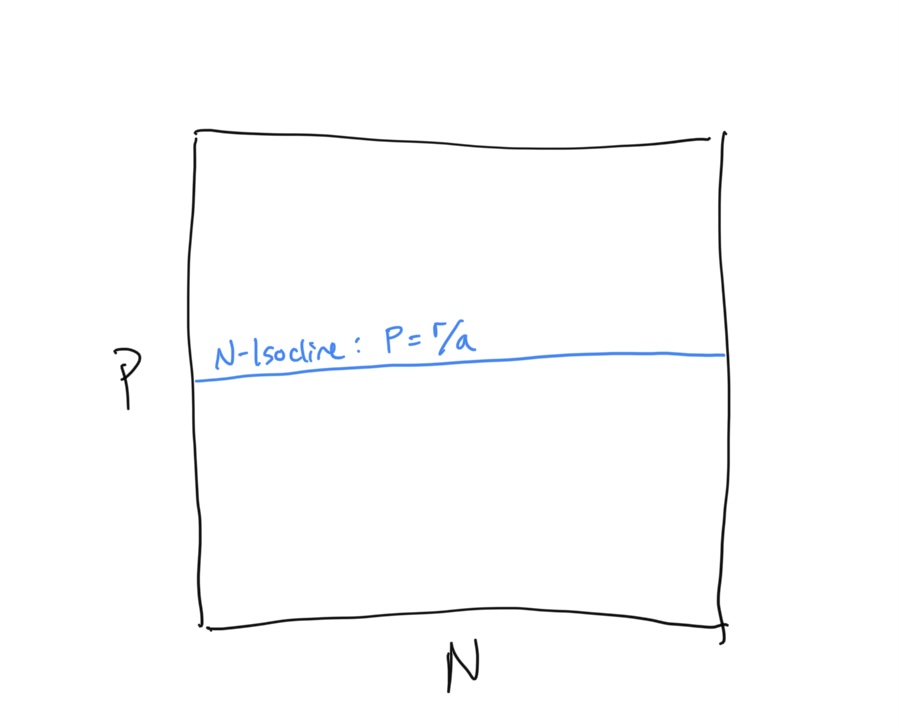

First let’s examine the prey population at steady state. To derive the \(N\) Isocline, we have

\[\begin{align} \frac{\rm d}{dt}N &= rN - aNP \\ 0 &= rN^* - aN^*P \\ rN^* &= aN^*P \\ r &= aP \\ P &= \frac{r}{a} \end{align}\]This is odd… our \(N\)-isocline is in terms of the predator population density \(P\). Keep this is mind.

Discussion

- When the prey population is at steady state \((dN/dt=0)\), the above relationship tells us where the population density of predators \(P\) falls. Given this relationship, how does a higher growth rate for prey influence the predator population density \(P\)? Provide reasoning.

- Similarly, how does a higher attack efficiency \(a\) influence predator population density \(P\)? Provide reasoning.

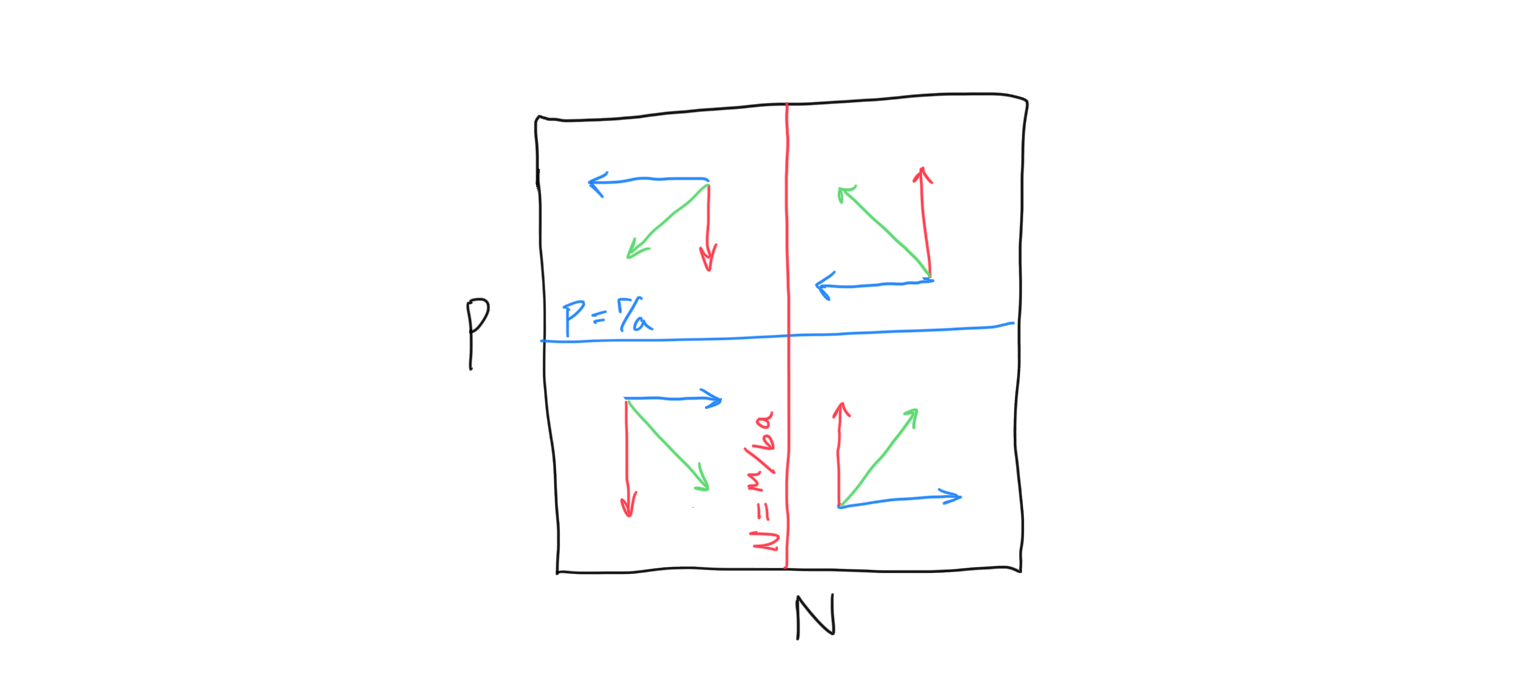

Let’s draw the the \(N\)-isocline in \(N-P\) space

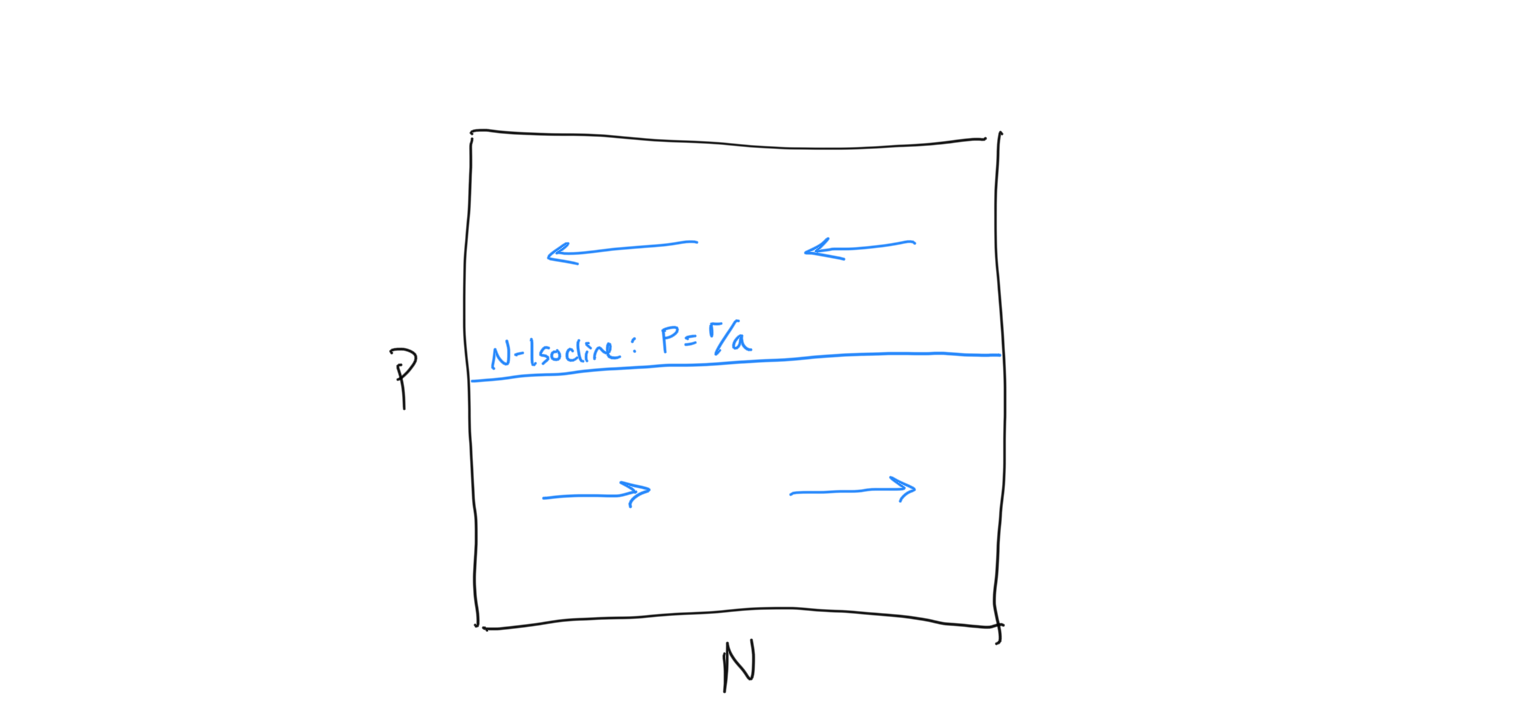

Now we need to determine the flow about the \(N\)-isocline. We do this using the same technique that we used for the competition equation. When we evaluated the competition system, we had some intuition about what was expected to happen because it built directly on the Logistic framework that we had previously investigated. Because this is a new type of system we have less intuition about how the flow should be arranged. Being very careful scientists, let’s evaluate the flow algebraically. First, let us ask when the prey population (because this is the prey isocline) is expected to increase… i.e. when is \(dN/dt > 0\)?

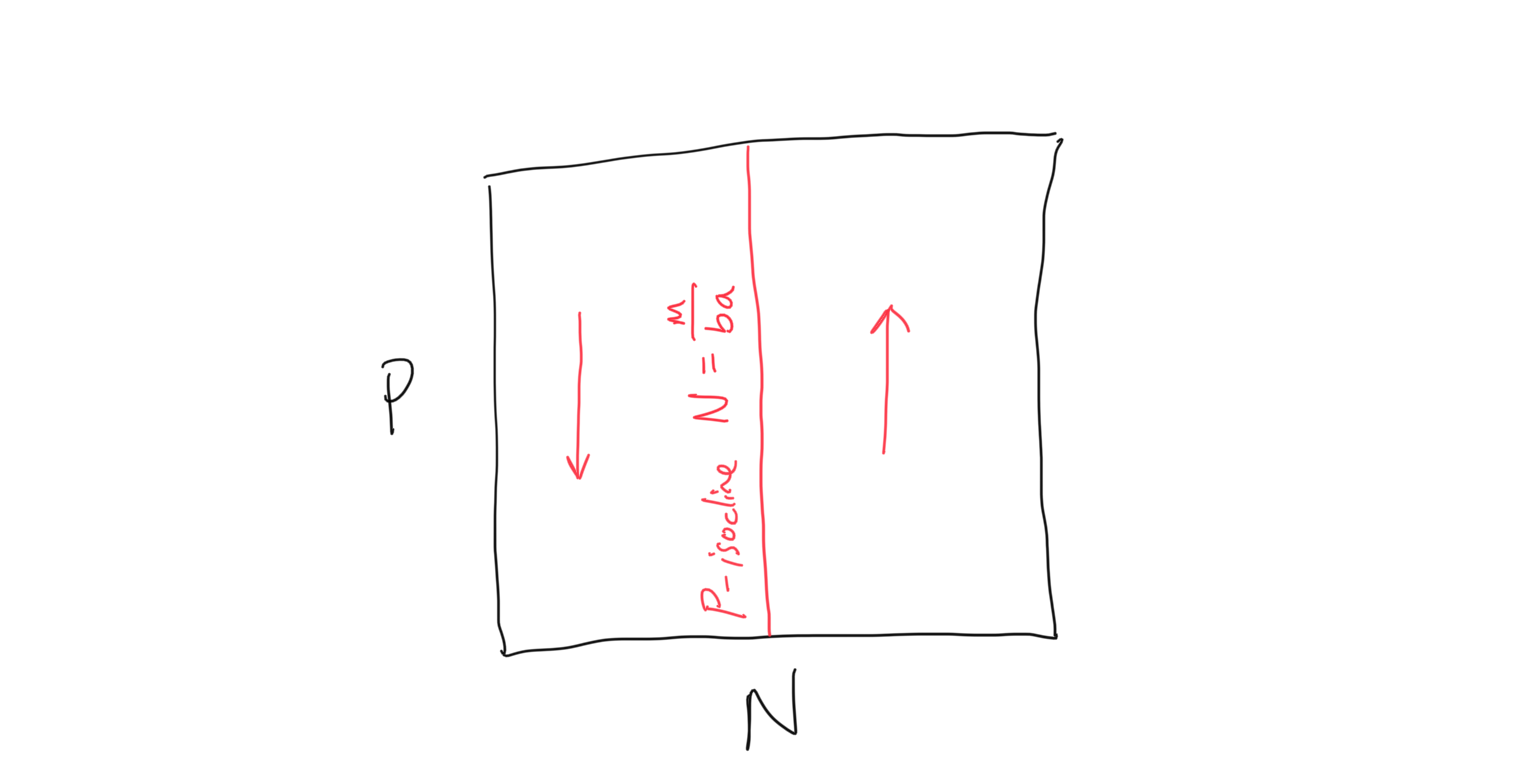

\[\begin{align} \frac{\rm d}{dt}N &> 0 \\ rN - aNP &> 0 \\ rN &> aNP \\ r &> aP \\ r/a &> P \\ P &< r/a \end{align}\]So when the predator density \(P\) is below the \(N\)-isocline, we have growth in the prey population \(N\). If we reverse the signs we are solving for the condition of prey population decline.\(dN/dt < 0\), which requires - unsurprisingly - that \(P > r/a\). Let us draw in the flow on either side of the \(N\)-isocline, keeping in mind that this is the flow of the prey population, which is horizontal along the x-axis.

Okay. Now let’s solve for our \(P\)-isocline, or the line along which the change in predator population over time is zero, i.e. \(dP/dt = 0\). To derive the \(P\)-isocline we have

\[\begin{align} \frac{\rm d}{\rm dt}P &= baNP - mP \\ 0 &= baNP^* - mP^* \\ baNP^* &= mP^* \\ baN &= m \\ N &= \frac{m}{ba} \end{align}\]Again we have something a bit odd… this is the predator, or \(P\)-isocline, but it is in terms of the prey density \(N\)! As we will see below, this will be a vertical line in our \(P\) vs. \(N\) coordinate space. Let’s now solve for the flow on either side of this isocline. Following the same steps as before, we will ask: when will the predator population be expected to grow, so that \(dP/dt > 0\)? So

\[\begin{align} \frac{\rm d}{dt}P &> 0 \\ baNP^* - mP^* &> 0 \\ baNP^* &> mP^* \\ baN &> m \\ N &> \frac{m}{ba} \end{align}\]Because the \(P\)-isocline is \(m/ba\), this is saying that when the prey population \(N\) is greater than the \(P\)-isocline, there is growth in the predator population. And as before the inverse is true as well: when the prey population \(N\) is less than the \(P\)-isocline, there is decline in the predator population. Putting this together we see that the \(P\)-isocline and flow can be plotted

Discussion

- When the predator population is at steady state \((dP/dt=0)\), the above relationship tells us where the population density of prey \(N\) falls. Given this relationship, how does a higher mortality rate for predators influence the prey population density \(N\)? Provide reasoning.

- Similarly, how does a higher attack efficiency \(a\) and conversion efficiency \(b\) influence prey population density \(N\)? Provide reasoning.

Now let’s put the prey and predator isoclines + flow together to determine the outcome of the LV predator-prey dynamics.

Discussion

- What are the final dynamics of the predator-prey system? On a sheet of paper, randomly pick a starting point and follow the flow. What happens?

- Translate these dynamics to a graph where you plot population sizes of the prey and predator on the y-axis against time on the x-axis. What pattern does this follow?

- Relate these expected dynamics to the Lynx-Hare system discussed in class. Are the LV predator-prey dynamics a reasonable mechanism for the observed Lynx/Hare population trajectories?

- What are the implications of these types of predator-prey dynamics with respect to the likelihood of extinction? Are populations exhibiting the dynamics expected from the LV predator-prey system ‘safe’ in terms of extinction risk? Why or why not?

- Solve for the point where \(dP/dt = 0\) and \(dN/dt = 0\). Will the system ever reach this point? If not, what is its significance?

Visualizing predator-prey isoclines and dynamics

Below is a code block where the Lotka Volterra predatpr-prey system is simulated. The main plot will show the predator \(P\) (red) and prey \(N\) (blue) isoclines, as well as the starting point and trajectory of the \(P\) and \(N\) populations over time (green circle and line, respectively). On the top right inset is a plot of the two \(P\) and \(N\) population sizes plotted over time. Make sure that you understand how the isoclines determine the flow and direct how the combined trajectories of \(P\) and \(N\) (green) change over time, and how this corresponds to the population sizes shown in the inset.

Try changing the values of the parameters. Based on your derived equations for the \(P\) and \(N\) isoclines, try to anticipate what the changes you make will do to the predator/prey dynamics.

library(RColorBrewer)

library(deSolve)

pal = brewer.pal(3,'Set1')

# Define the Rates function

pred.flow = function(r,a,b,m,Pstart,Nstart,tmax) {

# LV.comp = function(r1,r2,alpha,beta,K1,K2,N1start,N2start,tmax) {

yini = c(P = Pstart,N = Nstart)

fmap = function (t, y, parms) {

with(as.list(y), {

dP <- b*a*y[2]*y[1] - m*y[1]

dN <- r*y[2] - a*y[2]*y[1]

list(c(dP,dN))

})

}

times <- seq(from = 0, to = tmax, by = 0.1)

out <- ode(y = yini, times = times, func = fmap, parms = NULL)

Ptraj = out[,2];

Ntraj = out[,3];

timeline = out[,1];

Pend = tail(Ptraj,n=1)

Nend = tail(Ntraj,n=1)

maxtraj = max(c(Ptraj,Ntraj));

Psize = maxtraj*1.2;

Nsize = maxtraj*1.2;

p_isocline = m/(b*a); # = N

n_isocline = r/a; # = P

par(fig = c(0,1,0,1))

plot(rep(p_isocline,100),seq(-10,Psize,length.out=100),type='l',lwd=2,col=pal[1],xlim=c(0,maxtraj*1.2),ylim = c(0,maxtraj*1.2),xlab='N population',ylab='P population',lty=2)

lines(seq(-10,Nsize,length.out=100),rep(n_isocline,100),lwd=2,col=pal[2],lty=2)

points(Nstart,Pstart,pch=16,cex=2,col=pal[3])

lines(Ntraj,Ptraj,col=pal[3],lwd=2)

points(Nend,Pend,pch=8,cex=2,col=pal[3])

legend(0,maxtraj*1.2,c('P isocline','N isocline'),pch=16,col=pal)

par(fig = c(0.5,1, 0.5, 1), new = T)

plot(timeline,Ptraj,type='l',col=pal[1],xlab='Time',ylab='Pop. size',lwd=2,ylim = c(0,maxtraj))

lines(timeline,Ntraj,type='l',col=pal[2],lwd=2,)

}

# Plug in parameter values and run

pred.flow(r = 0.5, a = 0.01, b = 0.1, m = 0.1, Pstart = 70, Nstart = 100, tmax = 500)